|

The Brill Building

The Brill Building

When Neil

Sedaka's Breaking Up Is Hard To Do became the artist's first

Number One and ninth consecutive hit, the music business knew it had

to sit up and take notice of a significant new phenomenon - The

Brill Building.

Sedaka was

one of a close-knit group of songwriters and performers whose work

was becoming known as Brill Building Pop, after the building at 1619

Broadway, New York, where many music publishers had offices.

It was said

in the 30s and 40s that Tin Pan Alley was located just across the

street from the nearest dollar. This new Tin Pan Alley could be

located more precisely because in effect, the Brill Building had

become a production line for quality pop music, much of it under the

guidance of one man, Don Kirshner.

Kirshner's

first experience of the music industry had been in an unsuccessful

song writing partnership with the equally unknown Robert Cassotto

(who later changed his name to Bobby Darin and became a bona-fide

teen idol).

Kirshner

decided to take the energy of rock music and re-apply the

old-fashioned Tin Pan Alley disciplines of craft and professionalism

to the art of marketing hits for the youth market. With new partner

Al Nevins he formed Aldon Music - One of their first signings was

the song writing duo of Neil Sedaka and Howie Greenfield whose

Stupid Cupid provided a hit for Connie Francis in 1958.

|

As a solo

performer Sedaka then turned out Oh Carol, Calendar Girl, Happy

Birthday Sweet Sixteen and a string of others.

Sedaka's

ex-girlfriend Carole King was also brought onboard as a songwriter,

on a wage of $75 a week (along with her current beau, Gerry Goffin).

She was soon pumping out hits including Will You Love Me

Tomorrow? for The Shirelles, Take Good Care Of My Baby

for Bobby Vee, Crying In The Rain for the Everly Brothers,

and The Loco-Motion for Little Eva.

Kirshner's

next coup was a liaison with Barry Mann (writer of Who Put The

Bomp?). Teamed up with Cynthia Weil, the duo quickly scored with

Bless You by Tony Orlando, Uptown for The Crystals,

and You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin' for Phil Spector

protégés, The Righteous Brothers.

Describing

conditions in the Brill Building, Mann revealed "Cynthia and I work

in a tiny cubicle, with just a piano and a chair, no window. We go

in every morning and write songs all day. In the next room Carole

and Gerry are doing the same thing, with Neil in the room after

that. Sometimes when we all get to banging pianos, you can't tell

who's playing what".

And Aldon

Music wasn't the only publisher in and around the Brill Building.

Successful song writing teams Leiber and Stoller, Pomus and Shuman,

Bacharach and David, as well as individuals like Phil Spector and

Gene Pitney could all be found plying their trade at the Brill or

very nearby.

|

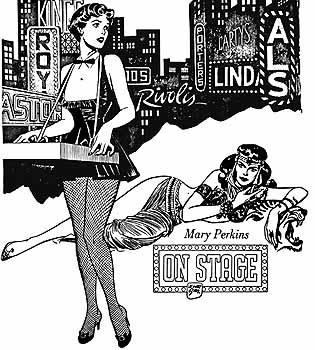

The Look of

Love: The

Rise and Fall of the Photo-Realistic Newspaper Strip, 1946-1970

The

well-crafted pop song. Think Brill Building at 1619 Broadway in

the early 60s and its Aldon Music counterpart across the street at 1650.

Lieber and Stroller. Phil Spector. Barry Mann and Cythnia Weil. Gerry

Goffin and Carole King. Hal David and Burt Bacharach. In the

tradition of the Great American Songbook, of Tin Pan Alley and Broadway,

these artists fashioned tremendously successful product that was

commercially sophisticated, elegant and simple, adult and

youthful in its pleasures. The

well-crafted pop song. Think Brill Building at 1619 Broadway in

the early 60s and its Aldon Music counterpart across the street at 1650.

Lieber and Stroller. Phil Spector. Barry Mann and Cythnia Weil. Gerry

Goffin and Carole King. Hal David and Burt Bacharach. In the

tradition of the Great American Songbook, of Tin Pan Alley and Broadway,

these artists fashioned tremendously successful product that was

commercially sophisticated, elegant and simple, adult and

youthful in its pleasures.

These composers before

Lennon and McCartney and Dylan were for the most part urban postwar kids

who had grown up across the Hudson and could see the Manhattan skyline

from their bedroom window. They loved traditional music forms but

infused with rock and roll spirit, youthful melodrama, swelling chords

and soaring melody.

The music they created was

under appreciated for years.

|

|

|

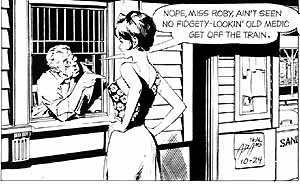

Our Man Rip It’s with real regret that

one realizes dailies used to look this good and may never

again. Alex Raymond, who had already once before revolutionized

comic art, manages the feat again with the evocative Rip

Kirby. Once, he had followed Matt Clark and John La Gatta

to create the sensual figurework of

Flash Gordon. Now the visually acquisitive Raymond turned

to the Cooper Studio fashion and advertising artists for

inspiration. High adventure, drama, romance came in a

spectacular daily blend of lush blacks, varied line work, and

bold composition. The late John Prentice ably continued on for

43 years after Raymond’s death in 1956, the strip lasting until

June 1999. |

Once,

there was the well-crafted story strip too. Once,

there was the well-crafted story strip too.

In Post War II America, mass

entertainment was in flux. Americans were restless. While Hollywood

vainly counterpunched with huge Technicolor Biblical epics, stark black

and white Film Noir and The French New Wave became the cutting edge in

film. Be-Bop intellectualized Jazz. The contrasting trends were

everywhere in fine art and Pop Culture. There were Free verse and the

Beats. Rock and Roll. Elvis. James Dean. Brigette Bardot and Bikinis. In

most media, Photo journalism was now king. Narrative radio was on the

way out and TV was on the way in. Readers, accustomed to years of the

immediate impact of visuals from newsmagazines, wire photos, and

newsreels, wanted real but a heightened reality set in the drastically

changed world around them.

American Illustration was changing too.

The first comic artist to show the new order was a familiar name for

innovation, Alex Raymond. He adapted for his new post War strip, Rip

Kirby, design concepts from the Charles E. Cooper Studio, concepts

which gave the impression of spur of the moment visuals --thereby

beginning the advent of romantic deep-focus realism to the pages of the

nation’s newspapers. New York art services which used comic strip

style ads, the most famous Johnstone and Cushing, made the Sunday paper

a line art billboard for a variety of products, ironically the work

looking more and more like the photographs they recently replaced. The

Poloroid instant camera, introduced in 1947, made photographed based

figure reference convenient and economically possible for artists on a

deadline and budget. For places and props, artists turned to, again

ironically, to huge clip files culled from the same magazines which had

used to feature hand-drawn illustration.

It

was a matter of career timing as well. It

was a matter of career timing as well.

The comic book and comic strip industry

had undergone some major shifts. Most likely the first of the

photographic, contemporary dress strips was Elmer Wexler's little seen

Jon Jason in January 1946 about an artist in South America, as it

shows (in the few panels I've seen) the move away from brush-inked

Crane-Caniff-Sickels impressionism which marks the old style, with Rip following three months later in March. (When

Jason

faded, Wexler ran to Cushing where he would stay long enough to pass

along his secrets and frustration with the form to a kid named Neal

Adams.)

with Rip following three months later in March. (When

Jason

faded, Wexler ran to Cushing where he would stay long enough to pass

along his secrets and frustration with the form to a kid named Neal

Adams.)

But there wasn't an immediate rush to

follow in Raymond's large footsteps. That took the mass exodus of

young second generation comic artists out of comic books in 1950 to

advertising and Madison Avenue. It was in these crucibles, among

them one headed by Lou Fine as well as the celebrated Cushing with Al

Dorne in its stable, where the young artists learned the discipline and

craft they would bring back to comic strips.

There

was no doubt that strips were where the action was. Comic strips were

still the high ground in the 50s. Not only were these artists

after Raymond following his lead by going to strips, but a nationally

syndicated strip was by far the most lucrative venue for a comics

artist. After Stan Drake makes his smashing debut with Juliet

Jones in 1953, taking only 18 months to match Raymond and Caniff in

circulation, we see the regular appearance of new photo strips for over

a decade. There

was no doubt that strips were where the action was. Comic strips were

still the high ground in the 50s. Not only were these artists

after Raymond following his lead by going to strips, but a nationally

syndicated strip was by far the most lucrative venue for a comics

artist. After Stan Drake makes his smashing debut with Juliet

Jones in 1953, taking only 18 months to match Raymond and Caniff in

circulation, we see the regular appearance of new photo strips for over

a decade.

Two genres especially benefited from the

glamour and idealization the style could bring on a daily basis--which

primitive network TV could not match for 20 years--the high adventure

strip, the detective or secret agent story, and the romance continuity,

the soap opera. The tight photographic style thrived for time and was

very influential overseas as well.

|

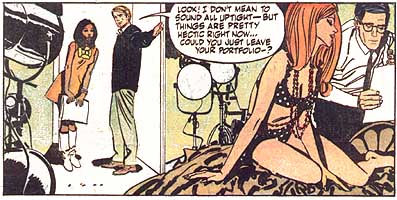

Stan Drake, a former advertising artist for Johnstone and

Cushing, set the standard for the romance strip. In The

Heart of Juliet Jones, Drake tried every line art device he

had learned, ransacked every trick of photo reference of his

profession, and even invented some to meet crushing deadlines

for 36 years with efficiency and elan. Other Cushing alumni

followed regularly thereafter, Leonard Starr and On Stage,

Ken Bald with three strips including Dr. Kildare, Alex

Kotzky and Apartment 3G, and Ben Casey with

precocious Neal Adams. Al Williamson kept the adventure strip

in step with his work on Secret Agent X-9 (later

Secret Agent Corrigan ). Overseas the style flourished

among many with Jim Holdaway on Modesty Blaise (later

Romero) and Frenchman Paul Gillon. The un-credited Teen

magazine clip art above shows how pervasive and linear the look

became in the 60s--and how slick even throwaways could be. Note

the crayon-like open line on the girl, the sketchy, fluffy hair,

the obligatory headband, dark expressive eyes and asymmetrical

mouth. |

Times

change, tastes change, but sales and deadlines are constant.

Created as a response to the competition embodied in television and the

movies, the photo-realistic strip couldn’t match the explicit sex and

violence or narrative pace that became standard in other media and

slowly began to die because the form required such relentless work on

the part of the cartoonist. Newspapers were fighting their own battles

for readers. Finally, declining syndication in the 70s meant less space,

both in prep and reproduction, which made the fine detail impossible,

even for the best artists. Times

change, tastes change, but sales and deadlines are constant.

Created as a response to the competition embodied in television and the

movies, the photo-realistic strip couldn’t match the explicit sex and

violence or narrative pace that became standard in other media and

slowly began to die because the form required such relentless work on

the part of the cartoonist. Newspapers were fighting their own battles

for readers. Finally, declining syndication in the 70s meant less space,

both in prep and reproduction, which made the fine detail impossible,

even for the best artists.

The form was strong enough to weather

many of the changes story strips endured, but not all. Some strips

continued on, notably Rip Kirby, Juliet Jones, and Apartment

3G. Others, like Ben Casey or On Stage, became a

pleasant yet distant memory.

They are largely forgotten in most comic

art surveys. But like the well-crafted song, the work endures and

deserves a closer look.

|

|

After the war, photo magazines featuring pin ups exploded in

popularity as well as their previously under-the-counter cousin,

the figure art photography periodical. These magazines before

Playboy not only offered a wealth of poses for swipes, but

helped fuel an amateur photography craze. From 1956 and Fawcett

Publications #318, Russ Meyer gives advice on tastefully

photographing well endowed women, including a demure (and

pregnant) Diane Webber. Pat Tourret and Jenny Butterworth's

Tiffany Jones was a true child of the 60s, in its heyday as

emblematic of the British Invasion in Pop Culture as Twiggy and

mini skirts. It was no surprise that Tiffany was a model.

Tourret herself was a product of the British romance and fashion

industry, but the pacesetters overseas were young Spanish

artists like Jose Gonzalez, Esteban Maroto, and Jorge Longaron.

Longaron's

Friday Foster, the first female black lead character in

American comic strips and an aspiring photographer as well, gave

America a brief glimpse of the Spanish take on the legacy of the

photo-realistic era and the changing roles for women the 70s

would bring. |

|